Lights Out: The Crucial Role of Dark Beaches in Sea Turtle Survival

Photography and Writing by Chris Jimenez

PUBLISHED AUGUST 2023, 15 MIN READ

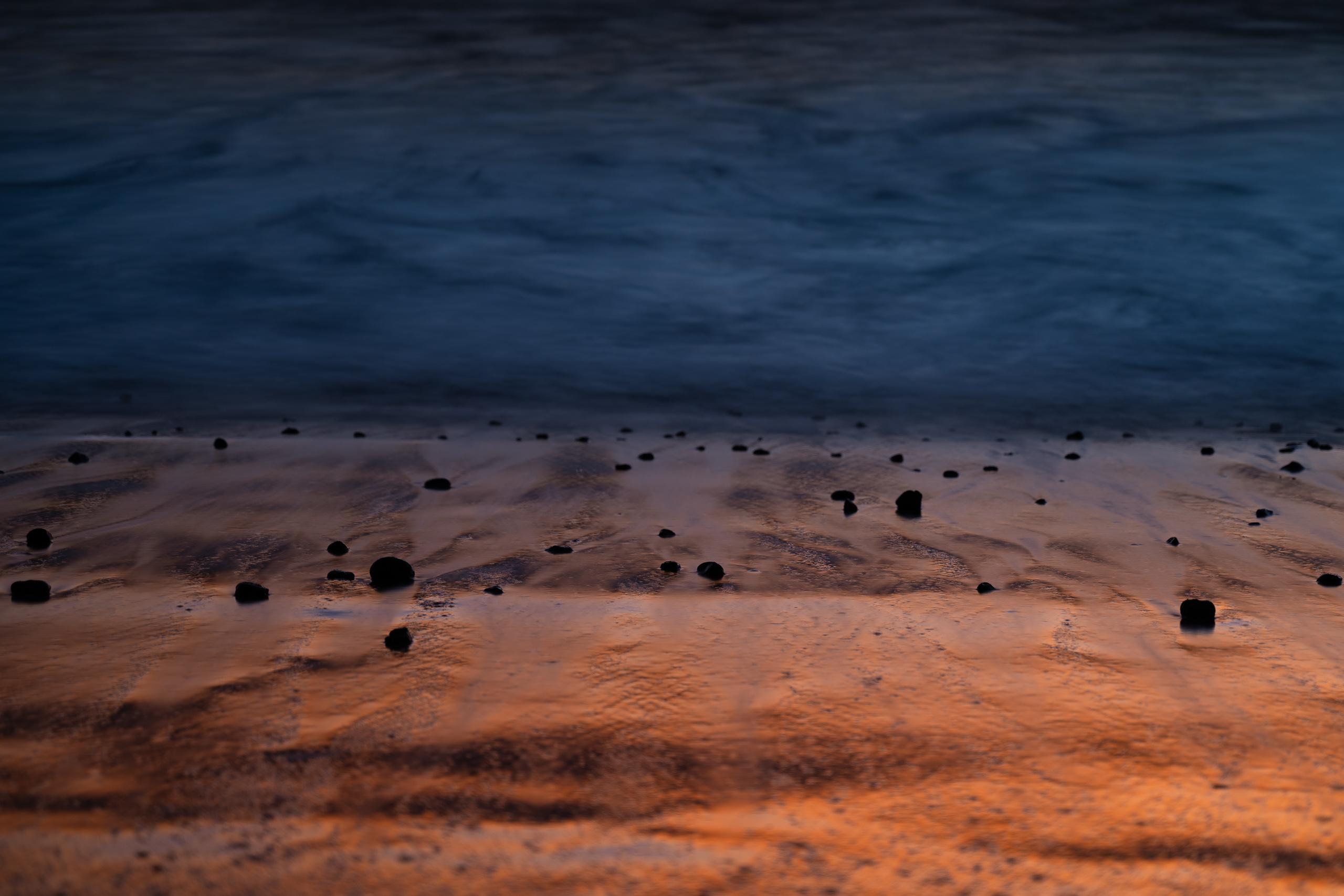

The coasts of Costa Rica are caressed by two seas, the Pacific Ocean on the west, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and these stretch out in long, unbroken swaths of sand that dance with the rhythm of the waves. Here, between the rush of the ocean and the whisper of the beach, the stage is set.

The Guanacaste coast of Costa Rica, stretching along the Pacific, is a landscape of profound contrasts. In the zenith of summer, the beaches are covered in soft, warm sand, ornamented by fallen leaves and speckled with shells. Sun-swept sands, turquoise waters, and thick coastal foliage mark this terrain by day, a vibrant palette dazzling to the senses. Yet, as the sun dips below the horizon, the land undergoes a transformation.

The burning oranges and purples of the evening sky dissolve into an expansive midnight blue, and the once lively beaches fall into a silent. The never-ending lullaby of the waves, the soft rustling of the palms, and the distant echoes of nocturnal life in the mangroves are the only sounds that break the serenity.

This obsidian night is not mere absence of light; it is a stage set for one of nature’s most incredible events. It is during these dark hours that the female sea turtles, having traveled thousands of miles across open oceans, find their way back to these shores, guided by a celestial compass ingrained within them since birth.

This is the territory of the sea turtle. Found in the warm waters and sandy beaches across the globe. The majority of these gentle giants that can be found in Costa Rica belong to four species: the Leatherback, the Hawksbill, the Green, and the Olive Ridley, each making the lengthy journey from hundreds of kilometres to the Costa Rican shores every year.

The Guanacaste region, named for its iconic Guanacaste tree, stands as a diverse and vibrant microcosm of Costa Rica’s larger ecosystem. Bordering the magnificent Pacific Ocean, it showcases a rich tapestry of tropical dry forests, mangroves, savannahs, and coastal landscapes.

It’s within Guanacaste that one finds an array of national parks, each with an unique interest for biodiversity.

The Santa Rosa National Park, for example, stands as a guardian of tropical dry forests, one of Central America’s most endangered ecosystems. It serves as both an ecological reservoir and a historical monument, preserving the relics of battles fought on this soil.

Rincon de la Vieja National Park, with its volcanic landscapes, bubbling hot springs, and dense cloud forests, offers a thrilling contrast. Here, the Earth’s fiery underbelly is made tangible. The park becomes a reminder of the relentless forces shaping our planet and the life that clings, adapts, and flourishes in even the most inhospitable terrains.

Then there’s Marino Las Baulas National Park, home to the sea turtles, and specially purposed for the awe-inspiring leatherback turtles. This park specifically caters to the conservation of these gentle giants, facilitating studies and public education about their nesting habits, life cycle, and the importance of preserving their dark nesting beaches.

Deep in the velvety blanket of a Guanacaste night, the dance of life begins. Buried beneath the warm sand, tiny cracks form on the surface of a sea turtle egg. The miracle of birth, long awaited, has arrived. A small flipper pushes out, feeling the cool sea air for the first time, a moment marking the beginning of a monumental journey.

The hatchling, smaller than the palm of your hand, shuffles its way up through the sand, embarking on the very first leg of its incredible journey. Emerging from the haven of the nest, the hatchling is immediately thrust into a world fraught with danger. It must race to the water, guided by the moon’s reflection shimmering across the ocean surface, avoiding prowling predators lurking in the shadows of the night.

In these defining moments, a race against time, nature, and odds is initiated, and the struggle for survival begins in earnest. Few will reach the safety of the open ocean.

As it hits the water for the first time, the hatchling is invigorated, its flippers paddling furiously against the push and pull of the tide. With this first taste of saltwater, it begins the ‘swim frenzy’, a marathon lasting several days, that will take it to the relative safety of the open ocean.

Once the frenzy subsides, the hatchling adopts a life in the pelagic zone, the open water, embarking on an extraordinary transoceanic journey that will last several years. It will grow and mature, braving the vast, treacherous ocean expanse, navigating complex currents, evading predators, and seeking sustenance.

Against a backdrop of relentless waves and under the watchful gaze of the sun, this humble voyager grows into a majestic adult, its shell hardening, flippers strengthening, turning it into an efficient marine traveler. Eventually, the now mature turtle embarks on a journey back to its natal beach. An internal compass guided by the Earth’s magnetic field directs this homeward pilgrimage, a feat of navigation that continues to baffle scientists.

Returning to the very same stretch of coast where it had once emerged as a tiny hatchling, the turtle completes a voyage that is nothing short of heroic. Here, beneath the moonlit sky, on the darkened sands of Guanacaste, the cycle comes full circle.

The female will lay her eggs, cover her nest, and then return to the sea, leaving behind the next generation to continue this extraordinary dance of life.

Sea turtles’ life cycle, their reliance on these nesting beaches, and their navigational prowess are all marvels of evolution fine-tuned over millions of years. A crucial element to this intricate web of survival is the darkness of the beach—a protective cloak under which the adult turtles can nest, and their hatchlings can safely make their perilous journey to the sea.

However, as the world encroaches upon their solitude, the turtles are finding themselves caught in a perilous paradox.

When darkness is threatened

Sea turtles are creatures of the night, preferring the cover of darkness for their nesting habits. The natural contrast between the illuminated ocean horizon and the dark silhouette of the coastal vegetation has long guided them to the right places. However, with the advance of coastal development in Guanacaste, artificial lighting is infringing on these untouched paradises, casting an unnatural glow over the beaches and causing disorientation among these sensitive creatures.

In the heart of Guanacaste, this fight between light and dark plays out each night. In the world of artificial illumination, the turtles find themselves on an unfamiliar stage, their age-old instincts disoriented, the natural cues they’ve relied on for millennia obscured.

Research has established that light pollution has adverse effects on sea turtle behaviour, most notably causing disorientation in both hatchlings and adult females. The distraction of artificial lights often leads them astray, away from the sea and towards danger. A plight that is not without significant ecological consequences.

One conservation project that is heavily involved in the area is KUEMAR. They are working on most beaches of the region between Playa Grande and Playa Flamingo, such as Playa Nombre de Jesús, Playa Real, Playa Honda, Playa Minas and Playa Roble. These beaches are not yet protected under the National Park or reserve status, and are among the last strongholds of good nesting areas for Green Sea Turtles, Olive Ridley, and even Leatherback Sea Turtles.

KUEMAR is a non-profit organisation which promotes conservation of marine turtles through research, outreach and voluntary work. It was founded in 2013 by two Costa Rican biologists who have been carrying out research on marine turtles, together with other conservationists, since 1994.

Through outreach activities, KUEMAR increases the awareness concerning the importance and the threats to marine turtles and the preservation of their coastal marine habitat. Students, tourists and local town inhabitants are the target audience, in order to enable them to recognise how marine turtles provide benefits to marine ecosystems and the local communities.

They also offers an opportunity for local, national and international volunteers to participate in beach patrols, the collection of data, the monitoring of sand temperatures and in outreach activities.

The Kuemar team has been tracking and creating data about the nesting females and their nests for more than 10 years, with a special focus on Green Sea Turtles. While the numbers have varied, there have been a stable numbers both females and nests year by year, with the exception of the COVID pandemic years of 2021-2022, where tourist travel and development were put on hold, and turtle nesting activities increased.

My family and I have been visiting the Playa Tamarindo area and its adjacent beaches for over 20 years, providing empirical evidence of its development. The region has experienced exponential growth in tourism and property development that may be considered even unsustainable. Hotels, restaurants, and nightclubs can be found on practically every corner of Playa Tamarindo. This beach is located just a few kilometres away from Playa Grande and Marino Las Baulas National Park.

Our experiences are in line with the data on Costa Rica’s investment in tourism.

This is the data of the Costa Rica Central Bank Tourist Development Satellite Accounts, that provides an official, objective and reliable measurement of the economic contribution of tourism.

The graph depicts the total number of businesses providing accommodation and food and beverage services, such as hotels, restaurants, bars, etc., and how it has grown over the years, except for the COVID pandemic period from 2020-2021.

Another source of data is the statistics provided by the World Tourism Organization, which allows you to compare a country’s tourism expenditure and arrivals year by year.

The Tourism Impact

Costa Rica’s natural wealth is a source of pride and identity, and the approach to sharing this wealth with the world has been crafted with foresight.

In Costa Rica, tourism should not be a mere transaction but an invitation to experience and respect the land, to engage with the local culture, and to leave behind only footprints and memories. The government and private sector should work hand in hand, developing strategies that promote environmental education, minimize waste, and empower local communities. The famed Certification for Sustainable Tourism (CST) is a testament to this cooperative effort, encouraging businesses to adhere to rigorous ecological and social standards.

In places where tourism has not been approached with care, the consequences have been stark and disheartening. Unregulated construction and deforestation have scarred landscapes, coral reefs have suffered from pollution and overfishing, and local traditions have been overshadowed by commercial interests.

One common occurrence in these beaches is the sight of hundreds of tourists being driven every night to the last remaining dark beaches to catch a glimpse of nesting turtles. However, most of these “tours” do not respect the distance to the turtles and simply come with the intent to pose with them and snap a few pictures. These tours are not regulated by any institution or conservation area, as they are outside of the Marino Las Baulas National Park.

After coming to the beach to nest, a green sea turtle looks out over the distant lights of tourists.

Lack of consideration and space towards nesting turtle is a common sight

Night and day

In the world of sea turtles, the contrast between shadowed beaches and those awash with artificial glow draws a line as stark as life and death. The darkened shores, untouched by human-made luminance, are the settings to which turtles have been attuned for thousands of years. Guided by the celestial brush of moon and stars, newly hatched turtles embark on their maiden voyage to the sea’s embrace.

Yet on shores invaded by lights, musics, streetlamps, buildings, and vehicles, a dissonance arises.

It is a tale of two beaches: one a cradle that rocks to the gentle rhythms of nature, the other a disorienting maze, where the man-made glow drowns the stars and confounds a journey that has graced the Earth since time unremembered. Here, in this reality, lies a poignant testament to the fragile balance of existence and the profound consequences of our choices upon those who share our world.

The following two beaches are just a few kilometers apart. From the air, the differences between them are quite striking.

After a failed attempt to nest, a green sea turtle turned back to the sea, disoriented by the lights and noises of hotels on the beach.

On these beaches is where the challenges of conservation become tangible and pressing. This beach, once untouched, stands at a crossroads, a delicate intersection between human ambition and ecological responsibility.

But the shadows of development loom large, a persistent reminder of the complex dialogue between progress and preservation. The concept of mixed-management parks holds a promise, a potential pathway to harmonize human needs with nature’s rhythm. Sustainable development in support of coastal ecotourism could indeed bolster resources for the park, fueling education, research, and community engagement.

For each nesting site lost to construction, each disruption in the delicate ecosystem, a thread is pulled from the intricate web of life that sustains both the turtles and the very soul of the region.

Conservationists, government agencies, and developers must tread carefully, finding common ground that serves both economic aspirations and ecological imperatives. The dance is intricate, demanding empathy, foresight, and the recognition that every choice leaves an imprint on the sands.

The very essence of Marino Las Baulas National Park, and indeed the broader Guanacaste coast, hangs in the balance. It is a living testament to the profound connection between land and sea.

The question remains: can this delicate harmony be sustained, or will the echoes of development silence the ancient song of the turtles? The answer lies in the choices we make today, in the courage to embrace a vision of development that honors, rather than overshadows, the timeless dance of life that plays out on the shores of Costa Rica. It is a vision that asks us to see beyond the immediate gains, to act as stewards, not just consumers, of the Earth’s treasure.

A green sea turtle waiting for the sun to go down so it can nest on the beach.

Green Sea Turtle Nesting in a Dark Beach

Guided by the moon, a green sea turtle emerges to lay its eggs on the beach.

Resilience

The story of a sea turtle’s life is one of resilience, tenacity, and survival against the odds. From a delicate hatchling emerging from the sandy nest to a powerful adult returning to the same beach, the journey of a sea turtle is a timeless testament to the enduring spectacle of life and the awe-inspiring intricacies of nature.

The problems of Costa Rica’s park system and sea turtles can be attributed to the government’s prioritization of economic development and profit over conservation of natural resources and wildlife protection. Additionally, the diversion of tourist revenues to development instead of conservation, lack of funding for parks, prioritization of tourist access over protection, and weak enforcement of conservation laws.

The only way to turn this around is to protect this last remaining patches of darkness, and to support the local institution of conservationist helping the turtles where it matters the most.

Only from these few beaches tracked by Kuemar, each nesting female of the green turtle is believed to lay, on average, 2.7 successful nests. With the recorded count of nesting females for the season, one can venture an estimate the number of hatchlings or newly born turtles birthed that season, a number that stands impressively at 58,000. This figure paints a tale of hope, signaling a potent contribution to the replenishment of the population. It stands as a testament to the meaningful impact of every conservation effort undertaken, especially when juxtaposed against the looming threats that sea turtles confront in today’s world. In this narrative, the perseverance of life meets the steadfast resolve of those who guard it, making every conservation stride not just relevant but essential.

Tiny sea turtle hatchlings with an incredible journey ahead of them.

Adapting to this encroaching changes is a monumental challenge, one that humans must assist in tackling. The response, though slow, is gaining momentum, with some resorts and coastal developments implementing turtle-friendly lighting, minimizing light spillage on the beach, and advocating for the importance of keeping conservation in mind.

During one of my last nights there, while I walked along the beach, I crossed paths with a Green Sea Turtle, her shell glinting under the sky. Against the backdrop of this cosmic theater, she carried out her primal ritual. As she receded into the ocean, her silhouette absorbed by the darkness, the beach returned to its tranquil state.

The conversation between the land and the sea resumed, as if never interrupted, the trails in the sand of the turtle were erased from the sand by the waves. It was as, if the Green Sea Turtle, had never been there at all.

All images in this website and any other source like Instagram, 500px, are © Copyright of Chris Jiménez & TakeMeToTheWild and available for license use. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Chris Jimenez and TakeMeToTheWild® with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

All images of this website are also Free to use for education or conservation purposes license. My images are free to use for any conservation and education purposes. You qualify if for example, you are an NGO or NPO, if you would like to use my pictures on your presentation or conservation website or in your school project. Please contact me explaining your use case.

Have a project in mind?

Get In TouchGEAR

The photography gear used in this story. Click on the items for more details.